- Quelle: Archiv Frau und Musik

- Gemeinfrei

Und sie spielten, sangen, komponierten und dirigierten doch: Die lange verschwiegenen Frauen in der Musik!

Kanonische Geschichtsschreibung und Wirklichkeit

„Das Weib schweige in der Gemeinde“1 – diese Paulus von Tarsus (vermutlich fälschlich!) zugeschriebene Äußerung hielt Frauen jedoch trotz dieses pauschalen Diktums nicht davon ab, zu singen, Instrumente zu spielen, zu komponieren, Musik zu unterrichten, Musik zu fördern, musikalische Nachlässe zu verwalten, Instrumente zu bauen, über Musik zu sprechen oder zu schreiben. Öffentliche Wirksamkeit und bezahlte Ämter bei Hofe, in der Kirche und in den bürgerlichen Kulturinstitutionen blieben ihnen jedoch bis ins 20. Jahrhundert hinein in der Regel verschlossen; die Musikgeschichtsschreibung hat sie kaum berücksichtigt.

Über singende Äbtissinnen, Troubadourinnen und Instrumentalistinnen …

Als früheste bekannte Komponistin des Abendlandes gilt Äbtissin und Poetin Kassia aus Konstantinopel (ungefähr 810–865), die eine eigene Frauengemeinschaft gründete und rund 50 Hymnen hinterließ. Es ist jedoch anzunehmen, dass auch vor ihr und mit ihr andere Frauen komponiert haben, von denen es keine Zeugnisse mehr gibt. Denn eine generelle Verschriftlichung der Musik setzte erst um 800 ein, die Zuordnung und Nennung von Autor*innenschaft noch viel später2 . Dies bezieht sich allerdings nur auf geistliche Musik, denn Lesen und Schreiben und insbesondere Notationskenntnisse wurde Frauen wenn überhaupt nur in Frauenklöstern und Konventen vermittelt.3 Im deutschsprachigen Raum war zum Beispiel Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) von Bedeutung, die mit ihrer Musik und ihren Visionen verstörte und begeisterte und deren Nonnen „an Festtagen beim Psalmengesang mit herabwallendem Haar im Chor stehen und als Schmuck leichtend weiße Seidenschleier tragen, deren Saum den Boden berührt“, was Magistra Tengswich des Kanonissinnenstiftes St. Marien in Andernach in einem Brief an Hildegard monierte.4 Die Hildegard-Forschung begann schon um 1900 und erhielt einen starken Schub durch die Frauenmusikforschung seit den 1970er-Jahren und zu den Feiern zu Hildegards 900. Geburtstag 1998.5

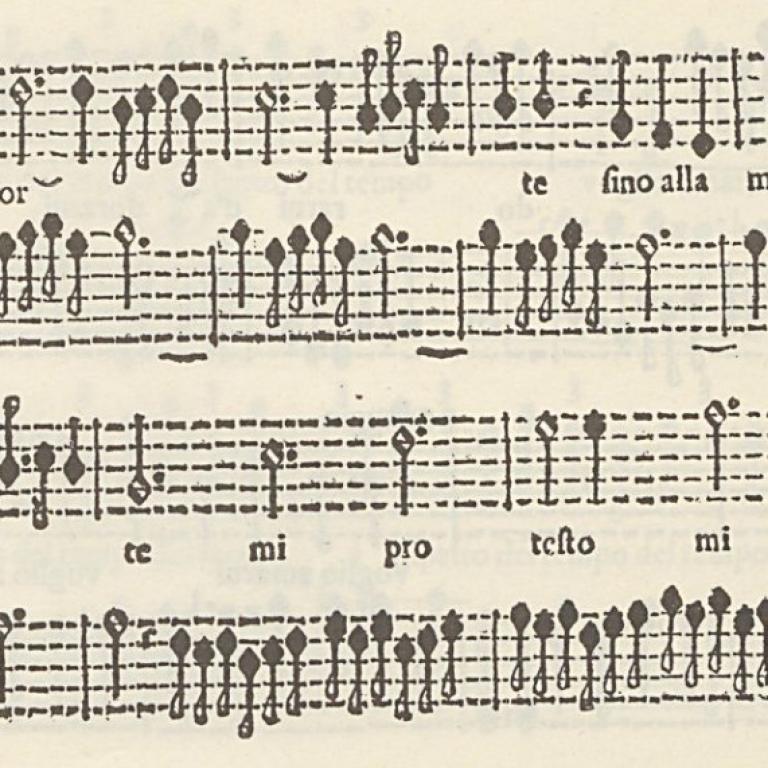

In der weltlichen Musik wirkten im Mittelalter zahlreiche Frauen als Trobairitz beziehungsweise als Troubadourinnen an portugiesischen, spanischen und französischen Höfen wie Beatriz de Dia (geb. nach 1140–unbekannt) oder N‘Azalaïs de Porcairagues (Lebensdaten unbekannt). Auch gab es Spielfrauen – Vagantinnen, Musikantinnen und Bänkelsängerinnen – die mit Musik oder als Tänzerinnen ihr Geld verdienten. Häufig wurde ihnen Prostitution unterstellt. In Italien lagen die Zentren für Musik von Frauen in der Zeit des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts unter anderem in Ferrara und Mantua, wo die frühbarocken Komponistinnen Francesca Caccini (1587–nach Mai 1641), Barbara Strozzi (1619–1677) und Maddalena Casulana (um 1544–unbekannt) wirkten sowie die Concerti delle Donne, Frauen-Ensembles, die erstmals die ‚wiedergeborenen‘ (griechischen) affetti (Affekte) wie Liebe, Hass, Trauer etc. auf der Bühne darstellten. Sie waren auch von Höfen engagierte Sängerinnen, Instrumentalistinnen und Komponistinnen in einem und außerdem maßgebliche Wegbereiterinnen für das neue Genre Oper.

… adelige Sammlerinnen, Mäzeninnen, Opernhausgründerinnen und Musikveranstalterinnen …

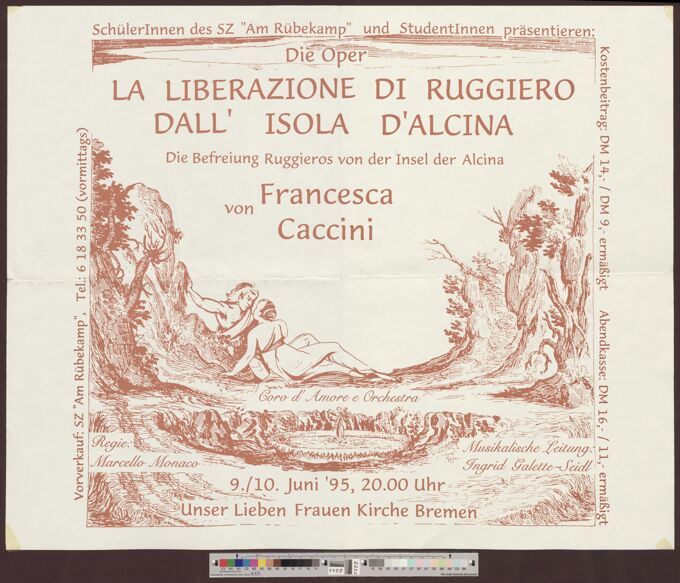

In der Zeit der Aufklärung hatten besonders adelige Frauen die Möglichkeit, auch schaffend zu wirken. So komponierte und musizierte zum Beispiel Anna Amalia von Preußen (1723–1787), eine Schwester König Friedrichs II. von Preußen (1712–1786), und legte eine Sammlung von Musikalien mit Werken Johann Sebastian Bachs (1685–1750) und dessen Söhnen und Zeitgenossen an. Auch ihre Schwester Wilhelmine (1709–1758) komponierte und ließ in Bayreuth ein Opernhaus errichten (heute UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe). Aus der Feder von Maria Antonia Walpurgis von Sachsen (1724–1780) ist die Amazonen-Oper Talestri erhalten, in deren Libretto und Komposition die Geschlechterrollen aufgebrochen werden. Auch in Francesca Caccinis (1587–nach 1641) Oper La liberazione di Ruggiero dall‘isola d’Alcina stehen die tragenden und zugleich machtvollen Frauenrollen im Vordergrund.6

Als Komponistin, Cembalistin und Mäzenin wirkte auch Anna Amalia von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1739–1807), die neben Musiker*innen einen Kreis von Dichter*innen und Gelehrten um sich versammelte – den ‚Weimarer Musenhof‘ –, zu dem unter anderem Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), Christoph Martin Wieland (1733–1813) und Luise von Göchhausen (1752–1807) zählten.

Ein wichtiges musikalisches Ausbildungszentrum in jener Zeit war Venedig, wo insbesondere Mädchen in Waisenhäusern eine umfassende musikalische Ausbildung erhielten. Für die Musikerinnen im dortigen Ospedale della Pietà komponierte unter anderem Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) zahlreiche Konzerte und Oratorien. Eine seiner Schülerinnen, die Musikerin und Komponistin Anna Bon (1738–nach 1767), wurde nach ihrer Ausbildung in Venedig mit ihrer Familie von Wilhelmine von Bayreuth an deren Hof angestellt.

… virtuose Netzwerkerinnen, Solistinnen und Primadonnen …

Da die Teilhabe von Frauen des aufstrebenden Bürgertums an Diskussionen im öffentlichen Raum kaum möglich war, luden sie nach Vorbild der Fürst*innen im häuslichen Rahmen ein, zu literarischen oder musikalisch-künstlerischen Gesellschaften und Zirkeln, später häufig Salons genannt. Als gefeierte Sängerinnen und Primadonnen findet man Frauen im 18. Jahrhundert an allen Theatern und Opernhäusern von Italien bis England, in Frankreich wie im deutschsprachigen Raum. Auch als Instrumentalvirtuosinnen reisten Frauen durch Europa, wie die Glasharmonika-Virtuosin Marianne Kirchgessner (1769–1808) und Maria Theresia Paradis (1759–1824).

… begabte Schwestern …

Für die Musikgeschichtsschreibung zählte insbesondere im 19. Jahrhundert das männliche ‚Genie‘. Die Protagonisten der neuen bürgerlichen Klasse konnten ihm den Glanz und dieselbe außerordentliche individuelle Leistung und übermenschliche Schaffenskraft zuschreiben, die sie für ihren Aufstieg und ihr Elitebewusstsein brauchten. Auch wurden die begabten Söhne der Familien konzentriert gefördert, die oft ebenso begabten Töchter mussten sich meist auf das schickliche häusliche Umfeld begrenzen. Prominente Beispiele sind die Familien Mozart7

, Bach8

und etwas später auch die Familie Mendelssohn Bartholdy:

War Fanny Mendelssohn (1805–1847) 1805 bereits mit „Bachschen Fugenfingern“9

geboren, wie ihre Mutter Lea Mendelssohn (1777–1842) nach der Geburt feststellte, so war der vier Jahre später geborene Felix (1809–1847) ebenfalls begabt. Er wurde jedoch nicht nur mit Fanny zusammen bestens musikalisch ausgebildet, sondern von Jugend an gezielt auf einen musikalischen Beruf vorbereitet. Für Fanny dagegen durfte, wie Abraham Mendelssohn (1776–1835) seiner Tochter 1820 zur Konfirmation schrieb, die Musik „stets nur Zierde, niemals Grundbass“10

ihres Lebens werden. Dennoch komponierte, musizierte und dirigierte Fanny Hensel bis zu ihrem frühen Tod 1847 und hinterließ ein Œuvre von fast 500 Werken, davon mehr als 300 Lieder für Klavier und Gesang, ihren begrenzten Aufführungsmöglichkeiten geschuldet.

… produktive Künstlerehen ...

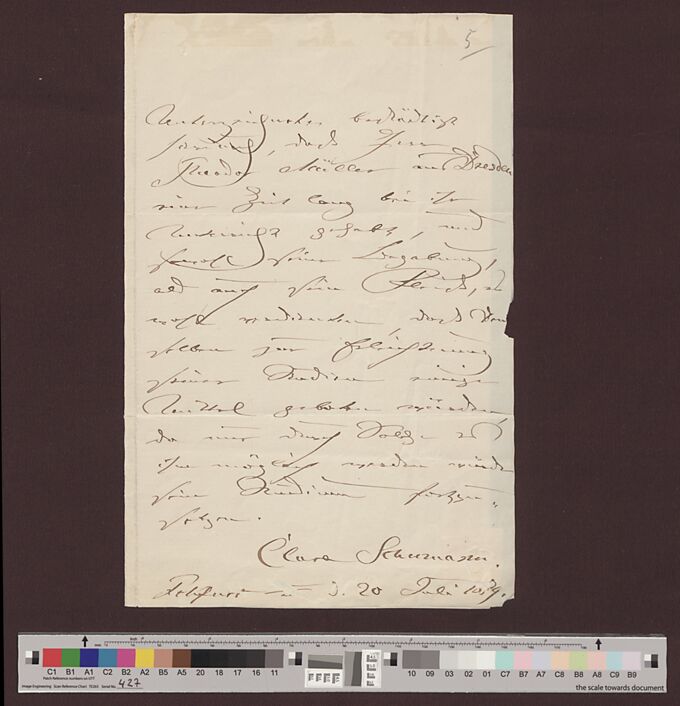

Ganz anders Clara Wieck (1819–1896), die als Tochter eines Klavierlehrers und einer Sängerin und Pianistin gerade nicht ausschließlich für das Eheleben, sondern als Berufsmusikerin ausgebildet wurde. Gegen den Willen des Vaters heiratete sie 1840 den damals noch weitgehend unbekannten Komponisten Robert Schumann. Ihr Komponieren blieb bald auf der Strecke, auch wenn ihr Mann sie anfangs dazu ermunterte. Grund zur Klage im gemeinsamen Ehetagebuch hatte Clara Schumann jedoch: „Zum Spielen komme ich jetzt gar nicht; theils hält mich mein Unwohlseyn, teils Robert’s Componieren ab. Wäre es doch nur möglich, dem Übel mit den leichten Wänden abzuhelfen, ich verlerne Alles, und werde noch ganz melancholisch darüber.“11 Trotz ihrer zahlreichen Schwangerschaften und acht Kindern verfolgte Clara Schumann ihre internationale Karriere als Pianistin weiter, führte stets auch die Werke ihres Mannes auf und machte sie dadurch bekannt.

… professionelle Komponistinnen, Dirigentinnen, Nachlassverwalterinnen und Pädagoginnen…

Von einem ehelichen Auftrittsverbot betroffen war die 1867 geborene amerikanische Komponistin Amy Beach (1867–1944), die mit ihrer Gaelic Symphony das erste in den USA entstandene Werk dieser Gattung aus der Feder einer Frau vorlegte. Erst nach dem Tod ihres Ehemannes 1910, mit dem sie eine von ihren Eltern arrangierte Ehe eingehen musste, ging sie wieder auf Konzertreisen. Aufgrund dieser offensichtlichen Behinderung ihrer Persönlichkeitsentwicklung wurde sie zur Frauenrechtlerin.

Auch die in Deutschland ausgebildete englische Komponistin Ethel Smyth (1858 1944) wirkte in der Frauenwahlrechtsbewegung mit. Mit dem The March of the Women (Text: Cicely Hamilton) schuf sie eine politische Hymne für die Bewegung, die auch heute wieder bei feministischen Veranstaltungen gesungen wird. Der Anführerin der Suffragetten, Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928), half das Singen dieses Marsches in schlaflosen Nächten, die Hunger- und Durststreiks im Gefängnis durchzustehen.12 Ethel Smyth komponierte neben Kammermusik und Chorwerken sechs Opern, von denen drei in Deutschland uraufgeführt wurden.

Ähnliche Erfolge konnte die in Friedland geborene Apothekertochter Emilie Mayer (1812-1883) erringen, die bei renommierten Komponisten studiert hatte. Sie komponierte neben Kammermusik auch große Orchesterwerke, die oftmals aufgeführt wurden. Zu Lebzeiten vielfach geehrt und als ‚weiblicher Beethoven‘ gefeiert, geriet sie nach ihrem Tod gänzlich in Vergessenheit. Erst durch die Forschung von Dr. Almut Runge-Woll13 wurden ihr Leben und ihre Werke wiederentdeckt und seitdem verstärkt wieder aufgeführt.

Um 1870 begannen Musikerinnen und Komponistinnen, sich auch in beruflichen Netzwerken zu organisieren. In Wien entstand der Club der Wiener Musikerinnen, der dafür sorgte, dass Berufsmusikerinnen und -komponistinnen erstmals eine Sozialversicherung erhielten. Bedeutende Mitglieder dieses Clubs waren zum Beispiel die Komponistinnen Mathilde Kralik (von Meyrswalden, 1857–1944) und Vilma (von) Webenau (1875–1953), die als erste Privatschülerin von Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951) gilt.14

Auch die französische Komponistin Lili Boulanger (1893–1918), die mit nur 19 Jahren als erste Frau den Grand Prix de Rome der Académie des Beaux Arts in Paris in der Sparte Musik gewann, war eine der ersten ‚Berufskomponistinnen‘ in Frankreich. Sie konnte einen Vertrag mit dem Verlag Ricordi abschließen und war finanziell unabhängig. Nach ihrem frühen Tod kümmerte sich ihre Schwester, die Komponistin, Dirigentin und Pianistin Nadia Boulanger (1887–1979), um ihren Nachlass und führte ihre Werke häufig unter eigenem Dirigat auf. Nadia Boulanger war außerdem eine gesuchte Pädagogin, die an vielen europäischen und amerikanischen Institutionen unterrichtete. Zu ihren Student*innen gehörten unter anderem Aaron Copland (1900–1990) und Marion Bauer (1882–1955). In den 1960er-Jahren brachte sie die Werke ihrer Schwester auf Schallplatten heraus. Die Kritiker reagierten begeistert: „Wir möchten mehr von ihr hören. Wir möchten wissen, was uns entgangen ist.“15

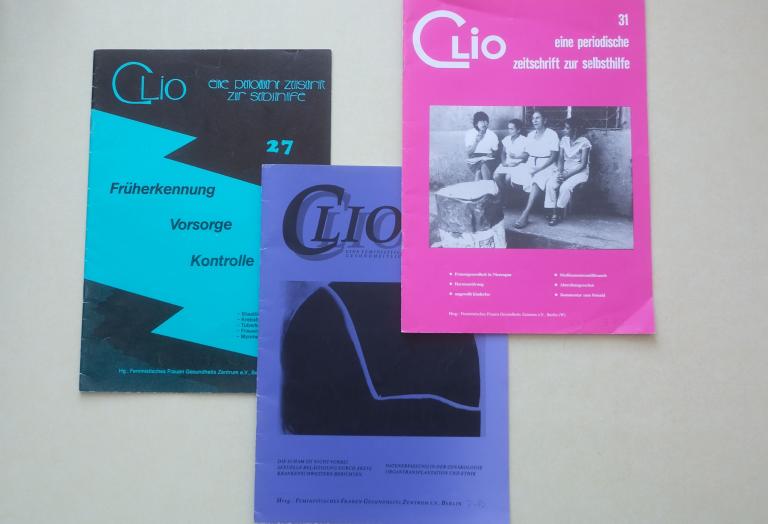

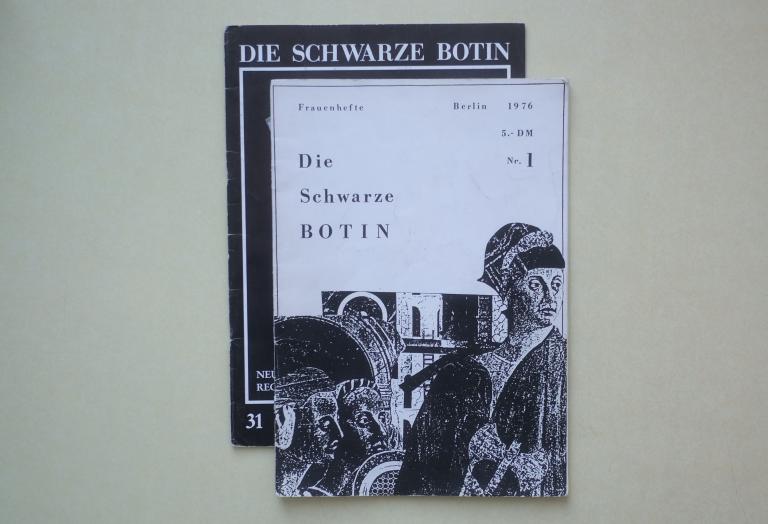

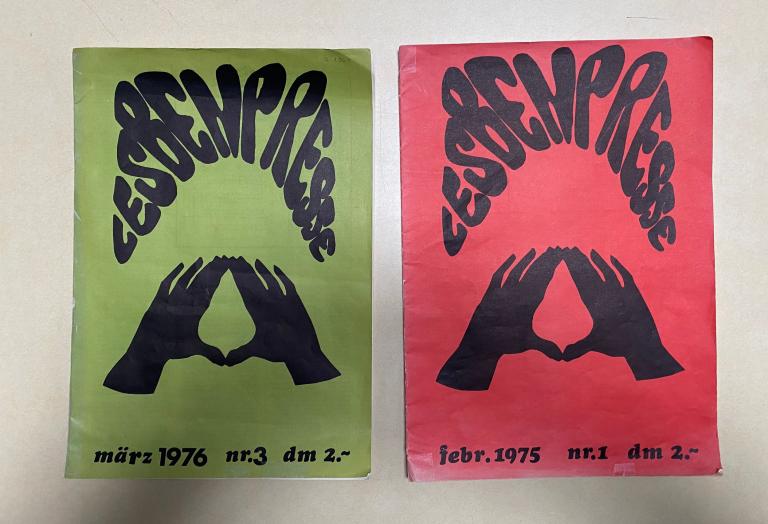

Die aus der Studierendenbewegung der 1960er- und 1970er-Jahre resultierende Frauenforschung sorgte dafür, dass dieser unbekannte, verleugnete und daher auch verkannte Anteil der Frauen an der Musikgeschichte wieder sichtbar und erlebbar gemacht wurde.

Fußnoten

- 1Paulus von Tarsus zugeschrieben: 1. Brief an die Korinther, in: Die Bibel, Kap. 14 Vers 34.

- 2Vgl. Nieberle, Sigrid: Stichwort ,Autorschaft‘, in: Kreutziger-Herr, Annette / Unseld, Melanie (Hg.): Lexikon Musik und Gender, Kassel 2010, S. 130 ff.

- 3Vgl. Koldau, Linda Maria: Frau – Musik – Kultur. Ein Handbuch zum deutschen Sprachgebiet der Frühen Neuzeit, Wien 2005.

- 4Zitiert nach: Führkötter, Adelgundis (Hg.): Hildegard von Bingen. Briefwechsel, Salzburg 1965, S. 201.

- 5Vgl. Kreutziger-Herr, Annette / Redepenning, Dorothea (Hg.): Mittelalter-Sehnsucht?, Kiel 2000, und Richert-Pfau, Marianne / Morent, Stefan J.: Hildegard von Bingen: Der Klang des Himmel, Köln 2005.

- 6Vgl. Fischer, Christine: Instrumentierte Visionen weiblicher Macht, Kassel 2007.

- 7Vgl. Rieger, Eva: Nannerl Mozart. Das Leben einer Künstlerin im 18. Jahrhundert Frankfurt a.M 1990.

- 8Vgl. Hübner, Maria (Hg.): Anna Magdalena Bach. Ein Leben in Dokumenten und Bildern, Leipzig 2004.

- 9Brief Abraham Mendelssohns an seine Schwiegermutter Bella Salomon vom 5.11.1805, zit. nach Hensel, Sebastian: Die Familie Mendelssohn 1729-1847 nach Briefen und Tagebüchern, 3 Bände, Berlin 191115, 1. Bd., S. 80.

- 10Brief Abraham Mendelssohns an seine Tochter Fanny vom 16.7.1820, zit. nach ebenda, S. 115.

- 11Vgl. Borchard, Beatrix: Clara Schumann. Ihr Leben. Eine biographische Montage, Hildesheim 2015, S. 150 f.

- 12Vgl. Brief von Emmeline Pankhurst an Ethel Smyth, 9.4.1913, in: Smyth, Ethel: Female Pipings in Eden, London 1934, S. 213.

- 13Vgl. Runge-Woll, Almut: Die Komponistin Emilie Mayer (1812-1883). Studien zu Leben und Werk, Frankfurt a.M. 2003. Im 2018 entstandenen Dokumentarfilm Komponistinnen (Deutschland, 95 Minuten) wird ihr Leben und Werk erstmals ausführlich dargestellt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_kf5SGrRPGU (deutscher Trailer).

- 14Wosnitzka, Susanne: „Gemeinsame Not verstärkt den Willen“ – Netzwerke von Musikerinnen in Wien, in: Babbe, Annkatrin / Timmermann, Volker (Hg.): Musikerinnen und ihre Netzwerke im 19. Jahrhundert, Schriftenreihe des Sophie-Drinker-Instituts, 12. Bd, Oldenburg 2016.

- 15Vgl. Blitzstein, Marc: Music’s Other Boulanger, in: Saturday Review, 28. Mai 1960, abgedruckt in: Léonie Rosenstiel: Lili Boulanger. Leben und Werk, Bremen 1995, S. 231.